‘they capture our greatest successes and our most profound losses’

text and photos by Emily Keen

“Necrophilia is not one of my failings, but I do like graveyards and memorial stones and such…” – Jan Morris

I don’t mind telling you that there have been times during this pandemic whenI have felt utterly lost. It happens so often these days that when I am trapped inside, I become removed from myself. During the days and months that have passed, worries about the future have filled my heart, and my mind is clouded with doubt. I was distressed because this is not the article I had intended to write, a fact that shouldn’t surprise me by now, or anyone else for that matter. Conspiracy theories aside, nothing about life during this pandemic has gone according to plan.

When I envisioned this article, I originally set out to write a guide to local history, urban exploration, and things that go bump in the night. A few unanswered phone calls and emails definitely took the wind out of my sails, but I was determined to spend a day exploring the older parts of our city, and to bring a part of it back to you. Sometimes, the things we need most in life are not the things we set out to look for, but rather the things that we find along the way.

On Friday, the 22nd of January, I found myself in need of perspective. Being that I was feeling rather solipsistic and morose, I naturally spent the day traversing some of the city’s oldest graveyards. I started with the Edmonton cemetary, and, later I went east to the Beechmount cemetary. If you’re still interested in ghosts, you would not be remiss in bringing a Ouija board or an EMF reader. I, personally, would recommend a picnic lunch and a good book for when the weather gets warmer.

When I first moved to Edmonton, I lived right around the corner from its eponymous and potentially oldest cemetery. It straddles the length of 107 avenue between 120th and 117th street. The cemetery was originally conceived as one space when it was founded in the 1870s, the north half is formally declared as the Edmonton Cemetery and the south half is the St. Joachim Catholic Cemetery. Which came first, the Edmontonians or the Catholics? Who can say?

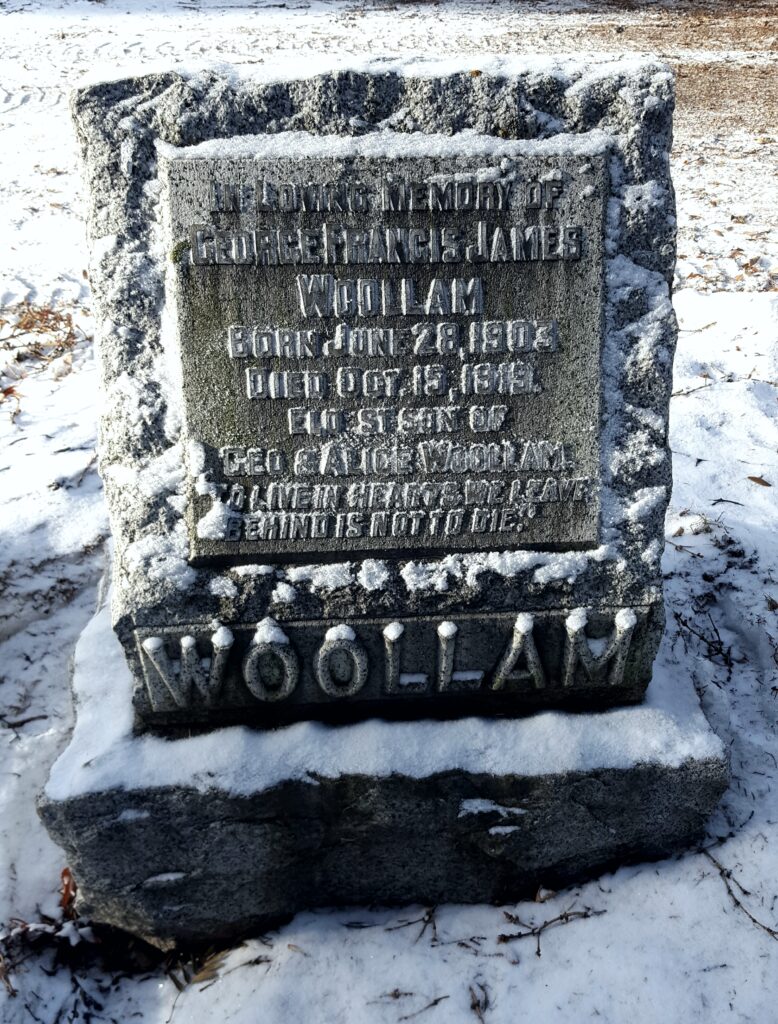

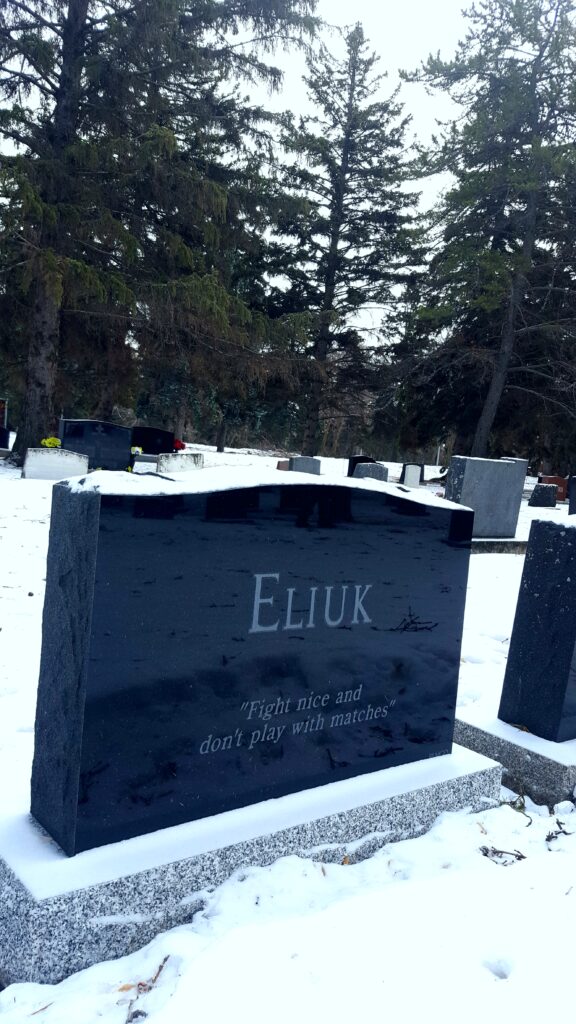

There is ample street parking on 106 avenue and one may make brief use of the parking lot outside Rosario’s karaoke bar on 108th avenue. From there, it is a shadowy walk down a path that makes its way beneath the towering frozen pines. There are headstones that range from sombre and gothic to sleek and modern with personal epitaphs. Some graves are so old here that even stone knows mortality, and those interred suffer a second death as their names are worn away by the passage of time.

The Edmonton Cemetery is home to many notable figures in the city’s history; there you can find names like Emily Murphy who was a member of the Famous Five, and partly responsible for winning women the right to vote in 1916. John Robert Boyle, in 1924, served as Justice of the Supreme Court of Alberta. Brigadier-General William Greisbach, was a veteran of the Second Boer War and World War I, whose incredible charisma made him the youngest mayor in the city’s history. Lastly, Gladys and Merrill Muttart – a couple whose incredible philanthropy and business sense is forever commemorated in the towering glass pyramids that stand in the heart of the river valley.

The wealth and stature of these people are reflected in the monuments that have been erected in their honour. Emily Murphy, in particular, resides in a mausoleum that has been christened “The Cathedral of Memories.” My particular interest, however, lies in the lives, and deaths, of smaller, everyday people. People like me.

I made a friend in the cemetery that day, her name was Mary. I was taken by the sight of her headstone, and her epitaph, “I did it my way” spoke to me on two levels as a headstrong woman and as something of a Sinatra fan. I wondered what it would be like to talk to her. I wondered how different our lives were, or if they were actually quite similar. I was certain that I could learn a great deal from her, she lived through two world wars and a pandemic.

A cemetery is a fascinating visual representation of a city’s history; it can tell you, on average, what kind of people lived there, how old they were when they died, and what was likely to have killed them. For the most part, cemeteries are a pleasant reflection of how we have grown as a society: people live longer, the city becomes more diverse, infant mortality rates decrease. In essence, they capture our greatest successes and our most profound losses.

On the west side of both the Edmonton and St. Joachim cemetery, stand row upon row of soldiers’ graves from the World Wars. The endlessness of it is troubling and vast, made only more so when considered as a small part of a much larger whole. It is strange to note how the older I get, the younger the dead seem to me, and I fear it not long until they become children to my eyes.

My travels took me east to the Beechmount cemetery, located south of the Yellowhead at 107th street. I was greeted by immeasurable swaths of soldiers’ graves and as I entered at the southernmost corner, that feeling of loss became even more profound. One could easily imagine them to be stone figures standing in eternal formation, struck down in the prime of their lives.

I made my way north on a snow plowed path that bisected the majority of the graveyard. As I neared the fence that separated this forested necropolis from the fury of the Yellowhead, I heard a strange sound. Defying the rush of cars whizzing past, was a soft sort of tinkling noise – the unmistakable sound of windchimes. Still unable to see the source of the sound, I broke from the cleared path and trudged through deep snow. My ears were my guide.

I found the windchimes fastened to a willow tree, along with pictures, mementos and toadstools that I did not have the heart to photograph. I had found a small, homemade shrine that had been dedicated to a lost child.

My solipsism had returned.

As I looked at this expanse of lived and unlived lives, I wondered how many secrets went unconfessed, how many hearts unshared, how many tears unwept. It came to me then that so many lives are perilously short, and so incredibly fragile; then, I arrived at the terrible and obvious realization that my own is not exempt.

The knot in my chest began to let go. Maybe it was the smell of the pinewoods, the fresh air and sunshine, but the troubles and worries that clouded my mind even an hour ago had been released. I had gained perspective, and this, above all else, is why I seek out the dead.

Edmonton has many fine cemeteries, some that are older still and some that reflect the growing and changing population in our diverse city. I spent a single afternoon in only two and I found things that interested and astounded me. During the summer, and when restrictions allow, there are guided tours available and I strongly recommend that you check them out, but for now, I encourage you to explore on your own. Who knows where your adventures will take you and the things that you will find along the way.