Review by Zachary Mann

There has never been a more delightful ballet than Frederick Ashton’s version of La Fille mal gardeé. It is an outstanding joy to watch, filled to the brim with endearing humour, complex and energetic choreography, and passionate dances such as the pas de deuxs (duets) shared by the two main characters, Colas and Lise. The Royal Ballet’s 2015 performance was available for viewing earlier this year on the Royal Opera House’s streaming platform, and is available to buy on their website.

La Fille mal gardeé is a romantic comedy set on a farm. It follows Lise (danced by Natalia Osipova), the young daughter of Widow Simone (Philip Mosley) who is determined to marry Lise off to the son of a wealthy landowner, Alain (Paul Kay). However, Lise (who loves a young farmer by the name of Colas, danced by Steven McRae) is uncooperative in Simone’s plan and spends the majority of the ballet attempting to break free from Simone’s grasp. Eventually, Simone has a change of heart and gives Lise and Colas her blessing, ending the ballet in their unification.

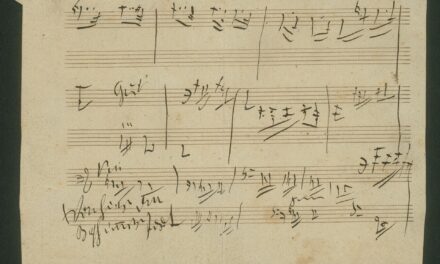

The original version of La Fille mal gardée premiered in 1789 at the Grande Théâtre in Bordeaux. Jean Dauberval, the choreographer, was inspired by Pierre-Antoine Baudouin’s painting Le reprimande/Une jeune fille querillée, which depicts a mother scolding her daughter while the daughter’s lover hides in the background.

The ballet was a widespread success and has since seen several revivals, the most notable one being Jean-Pierre Aumer’s 1804 version for the Paris Opera, scored by Ferdinand Hérold.

Frederick Ashton, the founding choreographer of the prestigious London-based Royal Ballet, was inspired by his love of the Suffolk countryside (his childhood home) which drove him to create a completely new version. The music for Ashton’s version was arranged and orchestrated by the Royal Opera House’s conductor John Lanchbery, using Hérold’s score as its foundation. Since its premier in 1960, Ashton’s version has become a prominent feature in the repertoire of various ballet companies across the world.

As the ballet begins, the curtains raise to reveal the painted backdrop of set and costume designer Osbert Lancaster – vast swaths of green and yellow rolling hills, a pond filling the foreground, and a few grazing cattle you can spot the distance – bathed in a hazy red morning light thanks to the work of lighting designer John B. Read.

A brush of white light illuminates five hens on stage as they shake themselves awake. After warming up their wings and legs for a few moments, they begin to dance. These hens alone should be enough of a reason to view this ballet; with their terre à terre steps (ground to ground, meaning quick and small) mixed between a flurry of allegro (quick and lively) jumps, the danseuses inside the feathery costumes perfectly embody the characteristics of a hen. Indeed, it is absurd, but this introductory dance was a pleasant primer for the following two acts.

From here we meet Lise, who radiates an adolescent exuberance the moment she steps out on stage. Natalia Osipova fits so naturally into the role that one would be led to believe that Lise is simply an extension of her own personality. Shortly after, we are introduced to Colas, who can only be described as the pinnacle of a charming male bravura. The two share a lovely pas de ruban, a stunning display of technical prowess in which Colas and Lise weave about a pink ribbon to show the lover’s knot tying them together. After a brief encounter with Alain, Widow Simone and Lise are carried off in a tiny trap pulled by Peregrine the pony to end the scene.

As we move away from the farm to a festival in the second scene of act one, we also move towards some of the more extravagant pieces of the ballet. Our two protagonists share the stage with the corps de ballet (“body of the ballet,” dancers who are a part of the company but not principal dancers or soloists) but still share some enchanting moments when they are the focus of attention, particularly an adagio pas de deux which displays some of their more elaborate partnering.

A favourite moment of mine is found during this piece – a tour de promenade (“turn in a walk”) performed by Natalia Osipova, held in place by nothing more than a ribbon she holds over her head. On the other end of this ribbon are eight danseuses who circle around her, slowly rotating her in the process to give Natalia the impression of a music box ballerina.

The highlight of this scene is the spectacular ensemble work of the maypole dance. Needless to say, any large ensemble piece is difficult to coordinate; but the ensemble of the Royal Ballet perfectly executes this jaunty piece which resides somewhere in between an English folk dance and classical ballet.

The costume design can also be seen in full force here. Shades of pastel pink, blue, green, and yellow from the jackets and dresses of the danseurs and danseuses intertwine as they dance about the maypole, creating a wonderfully intricate ribbon pattern which slowly descends from the maypole’s crown. It is a sublime display of colours reminiscent of spring and summer which proudly complements the high-spirited nature of the scene.

Act Two moves into Widow Simone’s farmhouse after a storm puts an end to the festival. It begins with Simone and Lise entering the farmhouse, which Simone quickly locks from the inside to keep Lise from escaping. However, Lise is not one to take no for an answer and attempts to steal Simone’s keys whenever the moment presents itself.

The scene is charming and endearing and Osipova takes full advantage of it, attacking the scene with a wide-eyed smile and a playful bounce in her step (not to mention her exceptional épaulement) which brings both her character and the choreography to life. Eventually, Simone leaves to fetch Alain for his and Lise’s wedding. Colas capitalizes on Simone’s absence and manages to smuggle himself into the farmhouse which marks the beginning of some of Colas and Lise’s more intimate pieces.

Between their mimicked movements and graceful, gravity defying lifts alone induces a near trance-like experience. Indeed, their interplay feels as if one soul has been split between the two of them.

Simply put, this ballet is captivating. The choreography is as extravagant as it is diverse, managing to seamlessly stitch together elements of English folk dance, clog dance, tap dance, and a maypole dance into the standard classical ballet repertoire. The execution of the choreography and acting is equally as brilliant, minus a few brief lapses in coordination during the ensemble pieces and a rather unwieldy lift during the first pas de ruban which are more than made up for by the outstanding performances given throughout the ballet.

Natalia Osipova emits a charming wistfulness as Lise which you cannot help but empathize with, Steven McRae brings the role of Colas to life as a strapping yet charming young farmer whom you cannot help but fall in love with, and the surrounding cast bolster the jaunty atmosphere of the ballet to the point of which you cannot help but feel as if you are a part of the ensuing action.

La Fille mal gardée is a welcoming ballet prepared to envelop you in its family of characters and would be a great place to start if you have never watched a ballet before.