A visually splendid, vocally powerful, and absorbing production of a favourite opera

Puccini: Tosca

Conductor: Simon Rivard

Director: Alison Moritz

Lighting Designer: Jason Hand

Chorus Master: Shannon Hiebert

Stage Designer*: Ercole Sormani

Costume designers*: Andrew Marley and Heidi Zamora

Cast:

Floria Tosca: Karen Slack

Mario Cavaradossi: David Pomeroy

Baron Scarpia: Peter Barrett

Cesare Angelotti: Peter Monawghan

Sacristan: Jin Yu

Spoletta: Zack Rioux

Sciarrone: Giles Tomkins

Jailer: Elliot Harder

Shepherd boy: Liz Flexer

Jubilee Auditorium

Saturday, October 22, 2022

*designed for the Seattle Opera production, and used by the Edmonton Opera production

When I read on Edmonton Opera’s web page that their production of Tosca, which opened on Saturday October 22, was set in 17th Century Rome, I was a little taken aback. Opera lovers are used to operas being rethought in more modern eras, but here seemed to be a production that was turning the clock back on the original setting by some 200 years.

Fortunately, this Tosca is actually firmly traditional, and is firmly – and splendidly – set in June 17 and 18, 1800. This makes full sense of the references to Napoleon Bonaparte apparently being defeated on Italian soil, swiftly followed by the news that he had, in fact, scored a huge victory over the Austrians at the Battle of Moreno on June 14, to the jubilation of all his Italian subversive supporters (two of whom play such an important role in the opera). One of the real strengths of Tosca is that audiences can easily imagine their own more contemporary parallels to a traditional production that they are watching, whether it be a political situation, or the abuse of power by a police chief.

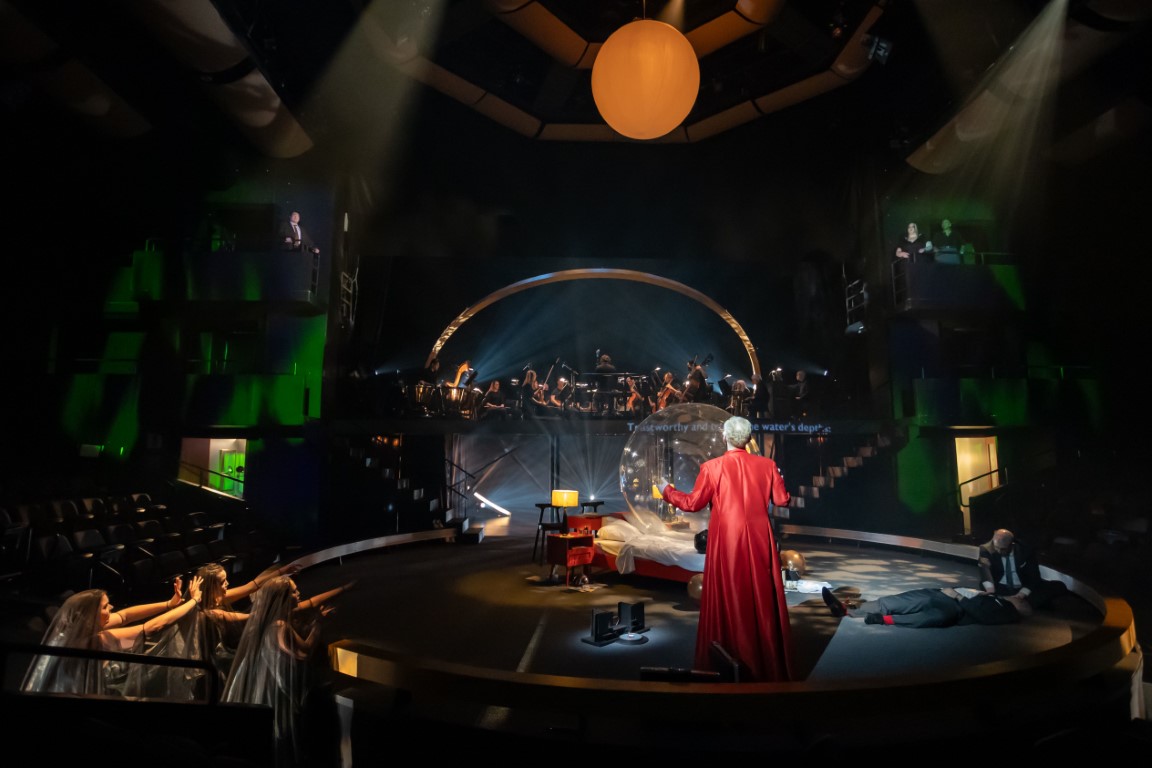

If you are going to present a traditional production of a favourite opera these days, then the first requirements for success are the set, the costumes, and the details of the stage direction. In all three areas this production triumphs – it is a visual delight, with sets created originally for Seattle Opera by Ercole Sormani, and costumes from Seattle Opera by Andrew Marley and Heidi Zamora. It is wonderfully directed by Alison Moritz, making her Edmonton Opera debut.

The church set for Act I is a panoply of baroque decoration and that heavy atmosphere that is so familiar to anyone visiting such an Italian church. The colours favour shades of browns, wisps of incense weave through the light from the windows. and the temptation to over-light it has been resisted, so there is a sense of an underlying darkness that entirely suits the opera. Above all, it places the main singers in exactly the right places acoustically on the rather difficult Jubilee stage.

That crepuscular feel to the church is brilliantly contrasted by the costumes for those who live and work in it, from the chorus boys to the church dignitaries at the end of Act 1, to the fashionable women walking through. Nothing extraordinary about this – most traditional productions strive for the same effect – but it is very well executed here, as is the beautiful lighting effects by lighting designer Jason Hand, for the rising dawn in Act Three. All combine to transport us to the Rome of 1800, complete with the cascade of Rome church bells, all in different tunings and timbres, as Puccini specified, and now thankfully made easier by the use of recordings.

Moritz’s production not only makes excellent use of these spaces, but is full of little details, such as the nuns crossing half unseen in the opening music, sentries appearing or disappearing at exactly the right moments, one of Scarpio’s minions turning away some tourists, or the very brief appearance of the non-singing Marchesa Attavanti being taken off to jail – there is such a strong sense of authenticity about this staging. She has also matched movements to the music, often very subtly but always very effectively, making one realize how theatrical this score is, down to its littlest details.

If you are going to do a traditional production of Tosca, then you also need three very large voices – all the more so in the cavern of the Jubilee – and this production has three such voices. David Pomeroy, no stranger to the Jubilee stage (his Calaf in Puccini’s Turandot in 2016 was memorable), is a convincing Cavaradossi. He is not the subtlest of singers, but his rich, dark voice has the kind of strength that suits the more heroic of the Italian tenor roles. He is matched by Peter Barrett as Scarpio, whose rich baritone and solid acting confirmed the promise of his debut in February’s La bohème. He is very convincing as the Police Chief organizing and ordering his men – the combination of his stage presence and some excellent stage direction makes us completely believe in his ruthless efficiency, and he does have an element of the sinister. He could perhaps have revelled a little more in his pleasure in sadism, and in the pain he causes Tosca – after all, he is the operatic successor to Iago (referenced in the opera) and the forerunner to Claggart in Billy Budd – and his performance has enough leeway to go quite a bit further before becoming overdone.

The Tosca, making her debut with Edmonton Opera, was the dramatic soprano Karen Slack. Here again is a huge voice – so powerful in her top notes in the last act of the opera.

The singing-acting characterization of the role, however, wasn’t really traditional at all. Tosca is almost invariably played with something of steel underneath the semi-flippancy and jealousy in the first Act. From Callas to the more vulnerable Angela Gheorghiu, you feel that they would under the right circumstances be perfectly capable of sticking the knife into the Marchesa Attavanti, should it ever be necessary. You don’t become a diva without a certain amount of metaphorical power-play. That makes sense: it is exactly the combination of flirtatiousness and yet underlying power that attracts such strong men like Cavaradossi or Scarpio. That still gives a lot of licence, from the aristocratic singer that is Raina Kabaivanska, whose self-reserve finally breaks down tragically, to Callas singing ‘Vissi d’arte’, where you get the sense not only of the pious woman asking why, but also that has she come to the realization that God has actually let her down.

Slack’s interpretation presents a rather different figure. She is flirtatious and full of petty jealousy in the opening act, rather like a spoilt child, but with little sense that she has any idea of the power politics going on around her. This naiveté is carried on into the second act, where more than anything else she seems to be bewildered by the circumstances she finds herself in – nor does she really react that much to what is happening in the dungeon, other than in the way one might expect an actress to do so in such circumstances. She is not helped here by the lack of any cries from that dungeon.

In other words, she comes across as rather superficial, until the realization of what is going to happen leads her to pick up the knife and kill Scarpio. This seems act an instinctive act prompted by her bewilderment (especially when she wanders around immediately afterwards). Her ‘Vissi d’arte’ is an entirely pious prayer of a woman who still doesn’t get it, and her placing of the candles either side of Scarpio’s body the act of a pious woman who still hasn’t understood the implications of what is happening.

It’s an interesting way of viewing the character. Certainly, it colours Act III, where she really does seem extraordinarily naive in her surety of how events will turn out. Thus her exhortations to Cavaradossi to act the role well brought laughs, rather than suggesting that here might be a woman who underneath is terrified that things might still go wrong. A vulnerable Tosca throughout, therefore, who never quite gets to grips with where she finds herself. By the end I found the interpretation got me re-evaluating, even if I did end up preferring a Tosca with more fire.

The supporting cast is universally well cast, with Jin Yu notable as the sacrosanct, and with strong acting discipling thoughout, in both the speaking and non-speaking roles.

The Edmonton Symphony Orchestra now set a high standard in their playing – some wonderful individual colours here. But (not for the first time) I personally wasn’t convinced by Simon Rivard’s conducting. It was perfectly workman-like, but it was pretty much all on one level, even in the loud moments, lacking any real tension. In other words, it wasn’t very theatrical, in an opera where the orchestra, as Moritz clearly knew, is very much one of the central protagonists. More dramatic tension from the pit would have taken this production to the next level.

That said, this is a compelling and absorbing evening, and if you have ever been told that opera is boring, go and see this production. It is a splendid baptism to Joel Ivany’s tenure as artistic director, and it shows that while Ivany intends to bring in more unusual operatic fare, he also knows what makes a really good traditional production.

Further performances

Tuesday October 25

Friday, October 28