by Milton Friesen

There are more than 700 people in Edmonton who live in tents or on the street. As winter comes, they will walk through wet snow and sleep at temperatures nearing forty below. They have nowhere to turn. The city’s shelters are already overflowing.

Many of these are severely drug-addicted – but do not think that they are a blight on Edmonton: rather, they are a mirror to our souls. Our attitude towards them reflects inwardly. It reveals our views on personal freedom, the value of life, and the nature of love.

I wandered our inner city, trying to understand the homelessness crisis. I sat down on street curbs, listening to incoherent stories from people with butane torches, needles, and glass pipes. I heard a middle-aged woman yelling obscenities at no one – or perhaps it was God, I could not tell. A young man in a stupor swung fists wildly into the air, fighting an imaginary foe. And I have been told other, more troubling accounts. A fragile, gray-haired lady lying in a ditch, clutching pieces of glass she called “her diamonds.” A fierce forty-year-old man scraping his head raw against the sidewalk, demanding that no one call the fire department. Open defecation on the streets.

These are the actions of the hurting.

“I want to do my own thing” was a phrase I heard repeatedly when I asked someone why they were staying on the street. Although it was left unstated, it was obviously implied that you can’t do drugs at a shelter. Indeed, 80% of the chronically homeless have drug or alcohol dependencies.

But that isn’t the whole story. Edmonton’s emergency shelters are over-capacity by 180 people. Faced with the choice between over-crowded group accommodation and privacy in a tent, it is not surprising the tent cities are growing.

The chronically homeless might not be saying no to drugs, but they don’t have the power to say yes to better choices either. Even if they chose to fight their addictions, they face long waitlists for detox beds, overcrowded shelters, and a lack of supported housing.

I often hear that it is impossible to help someone who does not want to change – that one must hit rock bottom and decide for themselves to improve. But these are people who cannot fall any further, except into a grave. If they are continuing to chose opioids and meth, then they are either not free, or the hope we offer them is bleaker than early death.

As I listened to their stories, it felt as if I heard the drugs speaking through them. They were hostages who were unable to express themselves freely, unable to make good choices.

The sad truth is that if someone is chronically homeless, they are unwanted by everyone who could provide them with a place to sleep. They have been thrown out by their families for society to deal with. The possibility exists that their families are unsupportive and cruel, but it is more likely that ongoing behavioral issues arising from severe addictions or mental health issues make hosting them difficult or even dangerous.

Society must respond, but how?

Many of us have lost all sense of the inherent value of life. Instead, we only value those who are brilliant, wealthy, or beautiful, and glorify the individual will. So, if a homeless person with pockmarked skin from their meth addiction is hell-bent on their own destruction, no one even cares. Our society tolerates dependence on drugs under the guise of allowing freedom of choice, but the message sent is clear – the addicted individual does not matter. They are not worth the cost or effort to intervene.

But this is profane and cruel.

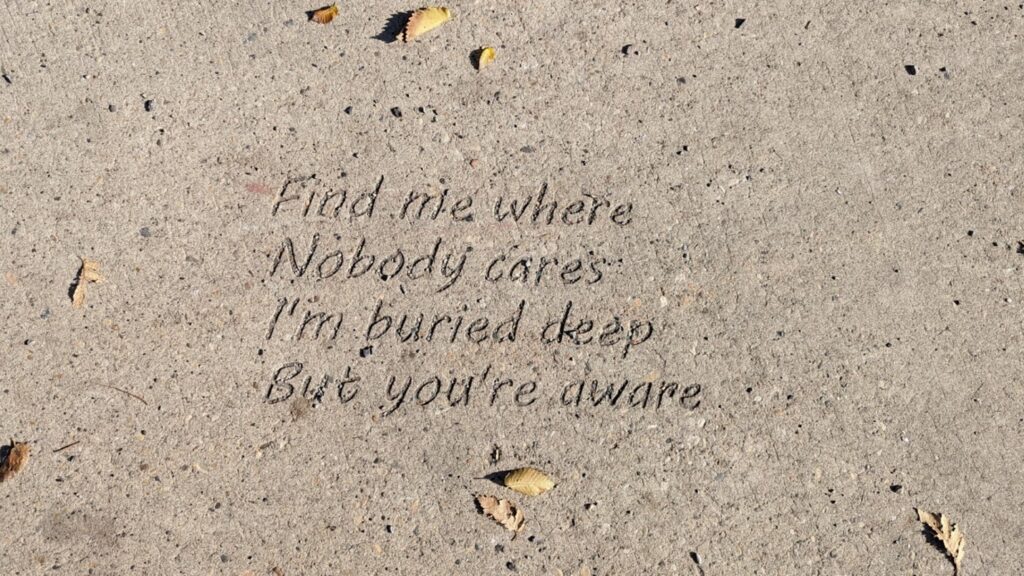

Sidewalk art near the Canada Post downtown depot

photo by Milton Friesen

They are worth our help. Not because they are so lovable, but because that which is noble calls us to be loving.

And they are worth helping beyond just providing safe injection sites, overdose response kits, or emergency beds in cold temperatures – the bare minimum to preserve life. What is more critical is secure housing, and free access to addictions recovery programs.

This will be costly. The amount the City of Edmonton has budgeted for community services such as affordable housing and homelessness has doubled from $70M to $140M between 2019 and 2023, and the problem has only worsened.

As a result, our help must not enable self-destructive behaviour by cutting a blank cheque for housing without compassionate intervention. Some will protest that this violates individual freedoms. But having enforced treatment for severe addictions does not strip someone of their liberty, it preserves it. It helps them regain independence.

The severely drug addicted struggle to navigate modern society. Something as simple as filling out an application form is a serious barrier. Initiating a conversation with a care provider is daunting, especially when battling deep shame, feelings of helplessness, or vivid hallucinations. Putting someone into rehab, even involuntarily, assumes that the most noble part of them wants to be free. They are just unable to get there on their own.

Tents along the street in McCauley

photo by Milton Friesen

But, together with intervention, our own attitudes must change. Our hearts must soften. We must become willing for low-income housing projects to be built in our own communities. We must become good neighbours. Our tight fists must be opened, and turned into generous, outstretched hands offering support and love.

If you are experiencing homelessness and need help with basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter, dial 211.

If you are in crisis, such as contemplating suicide, feeling overwhelmed, or experiencing abuse, call the Distress Line at 780-482-HELP (4357).

To support the homeless in Edmonton, donations can be made to Boyle Street Community Services.