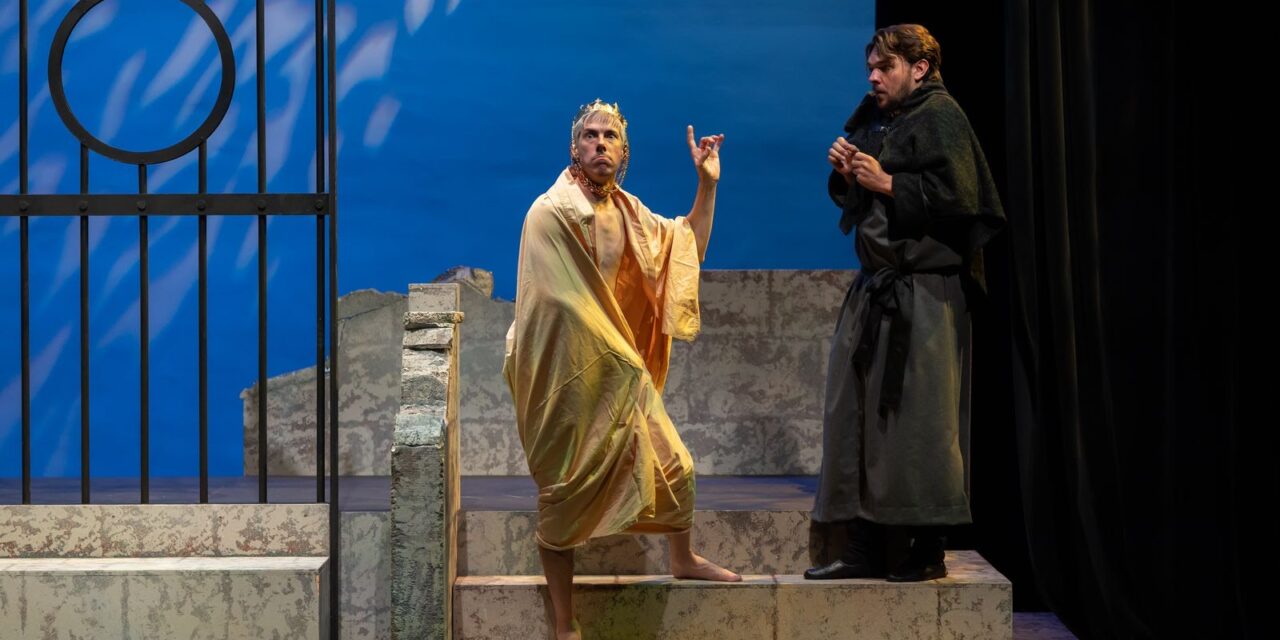

King Ethelred (Phillip Addis) and Roger (Clarence Frazer)

Review by Mark Morris

Photos by Nanc Price

Silence

Composer: Leslie Uyeda

Libretto: Darrin Hagen

adapted from the play by Moira Buffini

Directed by: Kim Mattice Wanat

Conducted by: Gordon Gerrard

Agnes (maid to Ymma): Rebecca Cuddy

Ymma (Princess of Normandy): Lara Ciekiewicz

Eadric (Ethelred’s warrior): Clarence Frazer

Roger (a Priest): Matthew Dalen

Silence (Lord of Cumbria): Teiya Kasahara

Ethelred II (King of the English): Phillip Addis

Orange Hub, Edmonton

June 21 -27, 2025

When the English playwright Moira Buffini wrote her fourth play, Silence, in 1999, it must have seemed pretty cutting-edge, and indeed it won the prestigious Susan Smith Blackburn Prize for best English-language play by a woman.

Its subject matter traversed not only millennium concerns, but explored emerging feminist ideas, including gender fluidity and identity politics. It was cleverly set in Britain in the reign of the Anglo-Saxon King Ethelred (Æthelred II, c.966-1016), when the Vikings were still a threat and Normandy was soon to become a force with the conquest by William of Normandy in 1066.

However, this merely provides a convenient backdrop to the events, and if the some of the six characters are based on real persons, there is little historical accuracy. Instead, Buffini uses the historical setting very much in the manner of Brecht, whose shadow stands behind the play. It uses absurdist elements to highlight social and personal concerns, and is structured in 27 short scenes that seamlessly flow into each other. Among its targets are the Christian Church (in the form of a priest, Roger, who is advisor to the King), the male gaze and sexual desire (personified in Eadric, the king’s right-hand warrior – historically Eadric Sreona, Ealdorman of Mercia), rape, violence against women, and their branding as witches, and, towards the end the usurpation of political power and the defeat of male domination by the two women characters in the play. There is even a magic mushroom (“mystic mushroom”) stew, just at a time when the hallucinogenics were undergoing a revival in popularity, thanks to the rave culture, and when it was still legal to possess fresh unprocessed magic mushrooms in the UK.

A Normandy Princess, Ymma, is sent to England to marry the Lord of Cumbria (in northern England), but finds that he has recently died, and instead she is wedding his son, a 14-year old boy called Silence. She discovers on the marriage night that Silence is actually a girl, something Silence has not been aware of. They then travel towards Cumbria, in the company of Ymma’s maid Agnes, together with Eadric, who falls for Ymma (and who himself had been raped as a child), and Roger, whose attraction to Agnes is reciprocated.

Meanwhile, King Ethelred, who by now also has designs on Ymma, has beaten them to Cumbria, where (we hear in reported speech) he has massacred the inhabitants, and violently put a witch to death. He now intercepts the travellers, captures Silence, has her killed by being thrown from a tower, and marries Ymma, who then murders Eadric.

Miraculously, Silence has survived, and, now dressed as a girl, masquerades as Ymma’s maid. Ymma lays down strict rules for the weak Ethelred to follow, rendering him a cuckold. For throughout the play, it has been clear that Ymma and Silence are attracted to each other, and it is equally clear they will continue the lesbian affair. Roger gives up the priesthood to marry Agnes.

If this indeed sounds somewhat absurdist, so it is. The satire and the social and political points are built on that absurdity. It is also very funny, even if the play gets increasingly darker. A Guardian critic aptly described the mood as “in turn Blackadder, Carry On, Monty Python and Shakespearean comedy” (1).

Buffini’s play was last seen in Alberta at the University of Alberta in May 2019. It was directed by Kim Mattice Wanat, as her MFA thesis production. Mattice Wanat is the founder and artistic director of Nuova Vocal Arts (formerly Opera Nuova). This year, their 26th Annual Vocal Arts Festival, running from May 31 to June 29, concentrated on music theatre, with productions of the 2022 musical Between the Lines (book by Timothy Allen McDonald, music and lyrics by Elyssa Samsel and Kate Anderson, based on the novel by Jodi Picoult), and Mary Rogers and Marshall Barer’s 1959 musical Once Upon a Mattress.

However, their third production was something of a departure: a new chamber opera, using established Canadian opera professionals. Nuova commissioned the Vancouver composer Leslie Uyeda to turn Buffini’s play into an opera, and they premiered it in the intimate and comfortable Orange Hub Theatre on June 21 (I attended the June 26 performance).

Uyeda is perhaps best known for her nine song-cycles setting the poetry of Lorna Crozier. Her new CD, The Sex Lives of Vegetables, which includes some of these songs, can be heard here. Her first opera, When the Sun Comes Out, to a libretto by Rachel Rose, was premiered at the Vancouver Queer Arts Festival (both Uyeda and Rose are self-identify as queer artists). It received a Toronto production by Queer Innovative Theatre in 2014, and was seen in a production by Portland Opera in 2022. Described as “Canada’s first lesbian opera”, it is (to quote Portland Opera’s publicity) a “love story following resistance against a fictional state that oppresses lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people. It centres on the rebellious Solana and her beloved Lilah, who is now a wife and mother; together, they fight for a new future, even as their secret romance is threatened by Lilah’s unpredictable husband, Javan” (who himself turns out to be gay).

The librettist of the new opera is the playwright, composer and Queer historian Darrin Hagen. This is his first libretto, though, as far as I could ascertain, almost all the text in the operatic Silence is taken directly from the play, apart – if I am correct – from some material at the end. The story is carried over completely from the play, without additions or omissions. Hagen’s task, therefore, was essentially to reduce the text to suit the demands (and slower speed) of opera, and it is skillfully done – it flows well, and I was surprised at just how much of the text he succeeded in including, without any sense of the opera being verbally overcrowded.

So how did Silence fare as opera?

A lot has, of course, changed since 1999. In the play, Silence herself is not presented as transgender, but as someone who had been born a girl, but told she was a boy, and brought up as a boy. This must partly reflect the then prevailing attitudes in the UK about trans people – the concept of gender dysphoria was little known generally, and so the character of Silence must presumably be seen as a more acceptable cypher for a concept whose overt expression might, at the time, have simply gone too far. In addition, of course, her character, once she learns she is a girl, allows presentation of a lesbian relationship in the play, at a time when prejudice against lesbianism was still strong in the UK: Section 28 legislation, introduced in 1988, prohibited local authorities (and thus schools) from intentionally promoting homosexuality, publishing material “with the intention of promoting homosexuality,” or promoting “the teaching of homosexuality as an acceptable family relationship”. It wasn’t repealed until 2003. Alberta, of course, has introduced legislation that, while not going quite so far, greatly limits the teaching about sex itself, let alone LGBTQ+ subjects.

The Sex Discrimination (Gender Reassignment) Regulations were introduced in the UK just after the play was premiered, and protected transgender people from discrimination in employment. This started a slow development of understanding: same sex civil partnerships were recognized in the UK in 2004 (my parents took advantage of this in 2008, my father having had gender reassignment surgery in 1972), the Equality Act 2010 further prohibited discrimination based on gender reassignment, and same-sex marriages were legalized in 2014. Canada still doesn’t have the equivalent of the UK’s Sex Discrimination (Gender Reassignment) Regulations 1999, but instead leaves the legislation up to the different provinces and territories. Thus the Alberta Government’s attack on gender dysphoria teenagers in Bill 26, and the Orwellian language it employs, is a Provincial decision, not a Canadian one. Same sex marriages in Canada were federally legalized in 2005.

Perhaps more pertinent, the public acceptance and understanding of trans people – at least in many social demographics in both the UK and Canada – has developed so far (as anyone teaching at a university, for example, can attest), however much we are currently seeing a backlash against the LGBTQ+ community perpetrated by governments in the States and in Alberta. Canada, since 2017, has prohibited discrimination based on gender identity and expression in areas under federal jurisdiction.

Thus the play stands on the cusp of changing attitudes to LBGTQ+, and of course is a blast against (and a satire on) traditional prejudices, and it does so in a very British tradition of barbed satire. Some of that is inevitably lost in a Canadian opera played to North American audiences – British audiences, for example, would instantly know King Ethelred’s nickname, even though it is not mentioned in the play: Ethelred the Unready, which in the play has pertinent sexual connotations.

Director Kim Mattice Wanat’s production is fast paced, entertaining, and often funny, mainly because of the humour inherent in the text. It flags only at the ending, to which, if I am not mistaken (I do not have access to the libretto), Hagen has added to change the emphasis from the Doomsday of the play (a pun on Domesday, that put the seal on the conquest of Anglo-Saxon Britain by the Norman William the Conqueror), to that of Silence finding her identity. The play has a number of false endings, which are carried over into the opera. They may well work in the theatre, but at the slower pace of opera, they became wearisome (“when is this going to end?”, one wonders), and the creators might consider adjusting this in any revisions. The music towards the end becomes more of a Broadway style – as self-identity triumphs – and the final quintet seemed to be without a trace of irony (unlike the ending of the play).

The ever versatile baritone Phillip Addis led the cast, playing Ethelred not as the “naked, scrawny youth” of the play, but as someone more mature, a kind of cross between Peter O’Toole as Lawrence of Arabia, and a character out of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. Soprano Lara Ciekiewicz as Ymma made a strong foil, creating a sense of sure continuity through the opera, both vocally and theatrically. Clarence Frazer was suitably gruff as Eadric, while Matthew Dalen conveyed the naïvety of the priest Roger. Rebecca Cuddy commendably managed to create a character out of Agnes, a role that is under-written in both play and opera.

This cast had a strong sense of ensemble, in part from a uniformity in acting style in what is inevitably a somewhat stylized opera. The exception was Silence, played by Teiya Kasahara. Kasahara had had a lead role in Uyeda’s first opera, and one got the impression, correct or not, that this new work was created very much with Kasahara as the central character. Certainly Kashara’s theatrical style was more histrionic, more theatrically self-aware, than the rest of the cast.

The opera was conducted by Gordon Gerrard, Music Director of the Regina Symphony Orchestra, whose association with Nuova Vocal Arts stretches back to 2000. The instrumentation is chamber sized: violin, cello, clarinet, flute, and percussion, with a notable contribution by percussionist Brian Thurgood. The neat set by Daniela Masellis created a very effective stylized multi-leveled playing space that, with a minimum of props, easily encompassed the swift scene changes, and included a clever set of boxes for the cart.

Uyeda’s score sounded as if it is grateful to sing (the vocal lines in her song cycles are also the most effective elements). It has to be said, though, that it was something of a disappointment. It skillfully keeps the pace of the theatre going, but the instrumental style is mainstream late 1950s chamber, tonal, with just that hint of the acerbity the late 50s mainstream would allow – it is as if post-Webern, the avant-guarde, the new Romanticism, the New Complexity, Minimalism, all the gamut of the last 75 years, had never happened. Uyeda likes ending passages by rising to a soft high note – one did not hear a firm loud one – which suited Kasahara’s vocal style very well (they float them very effectively, but one wondered if they could belt out a top ‘C’). As it was, there was little characterful (or memorable) about this music, however efficient it was in conveying the drama.

Fair enough, if that’s the style one likes, and it carried the theatre of the piece, but it really wasn’t what this libretto called for. One longed for something more cutting, something that matched the shock satire of the play: a 21st century equivalent of Kurt Weill. Equally, one wished that Uyeda would allow just a few equivalent of arias to emerge (she does have a couple of very conventional if effective sextets, including one to end the first half in traditional operatic style). There were certainly opportunities: there are a number of monologues and extended passages in Buffin’s play, but just when Uyeda would seem to have launched into song, it would not take flight but would revert to running along the ground supporting the drama.

However, there was another difficulty with this new opera, one more complex than questions of style of music or theatre. The play was written 26 years ago. The world has moved on since then, but this opera doesn’t seem to have done so. I wondered who exactly it is written for. It is very agenda-driven politically correct work, and will appeal to the converted. But surely the point of an agenda-driven work is to persuade those who are on the fence, or not conversant with the issues, or ignorant about the bigotry discussed and its effects. When the play was written, there were plenty to be so persuaded. But a majority of the Canadian population – and, let’s not forget it, a very sizeable percentage of the US population – has in that intervening quarter of a century, learnt to understand about gender diversity and acceptance of and tolerance for different individual, family, and social lifestyles.

But these days, an opera like this is not going to convert that opposite element of the population – and those in power in Alberta and the States – of the rightness of the message. If they ever saw it, it would probably do exactly the opposite, confirming them in their bigotry.

For the underlying messages in this opera, perfectly reasonable in a shock satire play in 1999, are really pretty bleak in the opera in 2025. Ymma commits murder and gets away with it in a lie. Roger abandons his spirituality. Ethelred is left to continue his vicious cruelty. A mature woman, Ymma, ends up in a lesbian relationship with a 14-year old girl, Silence. And the whole thing is so extraordinarily self-centered in its identity politics.

We have moved on to what is a much more dangerous phase in the fight for tolerance and equality, one where intolerance and inequality is not countered by questioning and the possibility of developing understanding, but is buttressed by a religious bigotry and social intolerance far stronger politically and socially in the USA and Alberta, and far more prepared to take extreme measures to stamp out its enemies. We desperately need new artistic works, new operas, to recognize the new realities and to fight against them. Silence belongs to the past.

Its message will, though, go down well in university opera workshops, where it will embraced by the converted taking part. Its size, its level of difficulty, its relatively simple staging, its small chamber orchestra, its ideal cast size, makes a university production easily possible.

But I am afraid that what unexpectedly came into my head at the end of Nuova’s production was not a line from the opera, but a famous line from a famous US president’s inauguration:

“Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country”.

Ask now. Domesday may well be upon us.

- The character most distorted from the historical model must be Ymma, in reality Emma, sister of Roger II, the Duke of Normandy. She was actually Ethelred’s second wife, and on his death married Ethelred’s enemy, King Cnut, eventually becoming Queen of England, Denmark, and Norway. She had considerable influence and power: she commissioned an account of herself, the Encomium Emmae Reginae, and, according to her biographer Pauline Stafford, she was at one point the richest woman in England.