Love’s Oblique Reflection

Review by Daniel Greenways

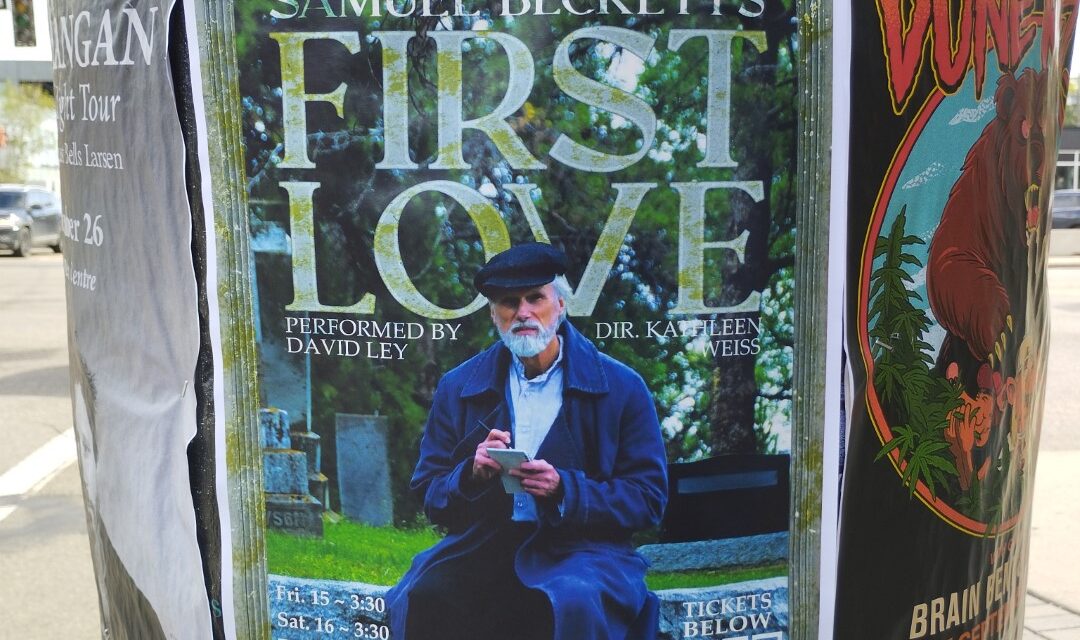

Written by: Samuel Beckett

Director: Kathleen Weiss

Cast: David Ley

Designer: Sarah Fett

Lorne Cardinal Theatre at the Roxy Theatre (Venue 32)

10708 124 St

to Aug 23, 2025

(Real) Runtime: 65 minutes

★★★☆☆

3/5 stars

There is a kind of anonymous pilgrimage that takes place every time a play by Samuel Beckett shows up in town. Rightfully so. Anyone who has combed through those mid-century writers who broke open the thin margin between high realism and absurdism knows that Beckett is one of theatre’s darkest crown jewels. The split in theatre that he catalyzed towards a theatre of the so-called absurd is often misunderstood as a kind of nonsense theatre of impenetrable pretention. If performed well, this couldn’t be further from the truth. In its rotten heart, Beckett’s work is not a divergence from reality, but a further investment into it. Absurdism, properly read, is hyper-realism of what dominates the real – the banal, absent and inescapable latency of one’s existence. Everything Beckett wrote hooks onto this line, presenting the world as a vacant space devoid of the grand meaning so often supplanted over theatrical narratives. His characters try to grab hold of their world, but it slips through their fingers, leaving a kind of absurd emptiness in its wake.

Those who like to meditate on such ideas should find their eyebrow flying to their foreheads whenever they see Beckett’s name show up in a Fringe bulletin. Some of those flying eyebrows led a medium-sized crowd down to the Roxy this afternoon. However, even the most ardent fan of Beckett’s work would be forgiven if they did not recognize a play called First Love, because Beckett never wrote such a play. Instead, he wrote a short story in French called Premier Amour in the 1940s, which was published about thirty years later in English. This is where the complexity of this performance begins. Kathleen Weiss’ production is not the first to stage First Love as though it were a work of Beckett’s stage repertoire. Many readings have been put up in the French-speaking world, and a few in English, including an adaptation by Ralph Fiennes. The Edmonton performance was not really an adaptation, in the full sense, as it seems the reading was performed word-for-word.

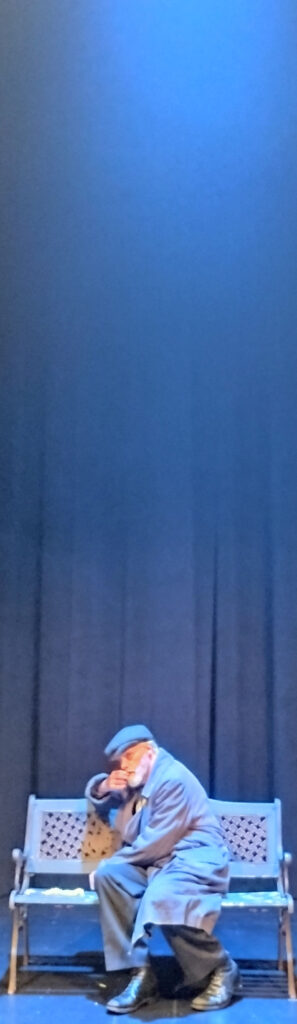

The story of First Love is a kind of broken mirror. It is the internal monologue of a man reflecting on a fraught relationship he had with a woman named Lulu. He describes the way that their meetings led to a cyclical pattern of desires and choices that have haunted him since they met. Partway through the play, Lulu is revealed to have been a prostitute, but we never get a clear view of her character. Though she is the object of many descriptions, the real subject of the story is the main character’s conflicted experience with love and sexual desire. As he dissects the incompatibility between these moods, we encounter every Beckettian trope – natality and mortality, mounds of earth and trash, biblical and literal fathers, pessimism and misanthropy, barren trees and even a park bench (which is the only set in this production). Like many of Beckett’s tramps, the main character is a kind of existential vagabond, wondering where he could lay down roots in a concrete world. The only solace he finds are moments in a graveyard, saying that his sandwiches and bananas “taste sweeter when I’m sitting on a tomb”. He even spends some time writing his own epitaph, as though he might be able to fix his life in place if only it were determined by such a stone.

David Ley brought this character to life with fluidity, laser-focus, and remarkable memory. His character was especially evocative of the unsettled, wavering mannerisms in Beckett’s text. However, the one-man performance was burdened greatly by the play’s descriptive tone. Because First Love was actually a novel, it is entirely comprised of a passive monologue, and it is more characteristic of Beckett’s neurotic prose than his absurdist dialogue. As such, Ley’s role as an actor is a mountainous climb. The tendency to rattle off text as a typewriter is strong here, and the play would have benefitted immensely from more space for silence and thought. Beckett’s writing is so verbose and literary that there is a tendency to perform his work intellectually. Unfortunately, this is the opposite of what is needed. The audience needs even more emotional range to offset the incumbent dryness. Ley’s performance lacked a bit of this dynamic range. Instead of a confusion of desires, we saw desire presented as confusion. One wished that the character was less lucid, less sober, more broken.

In the end, as is so often the case, the play’s meditation on love made up for most of its limitations. The audience seemed quite moved by the poetry and openness of the whole spectacle. If you are a fan of Beckett’s writing, you should try to see it while it is here.