Ukraine’s Mobile X-ray Booth Arrives at the Edmonton Fringe

Review and photos by Daniel Greenways

Written by: Natalia Blok

Directed by: Lianna Makuch

Production Design by: Stephanie Bahniuk

Stage Management by: Lore Green

Sound Design by: Bernardo Pacheco

Graphics by: Amelia Scott

Produced by: Sheiny Satanove

Starring: Geoffrey Simon Brown, Mariya Khomutova, Anna Kuman, and James MacDonald

Dedicated to the memory of Julien Arnold

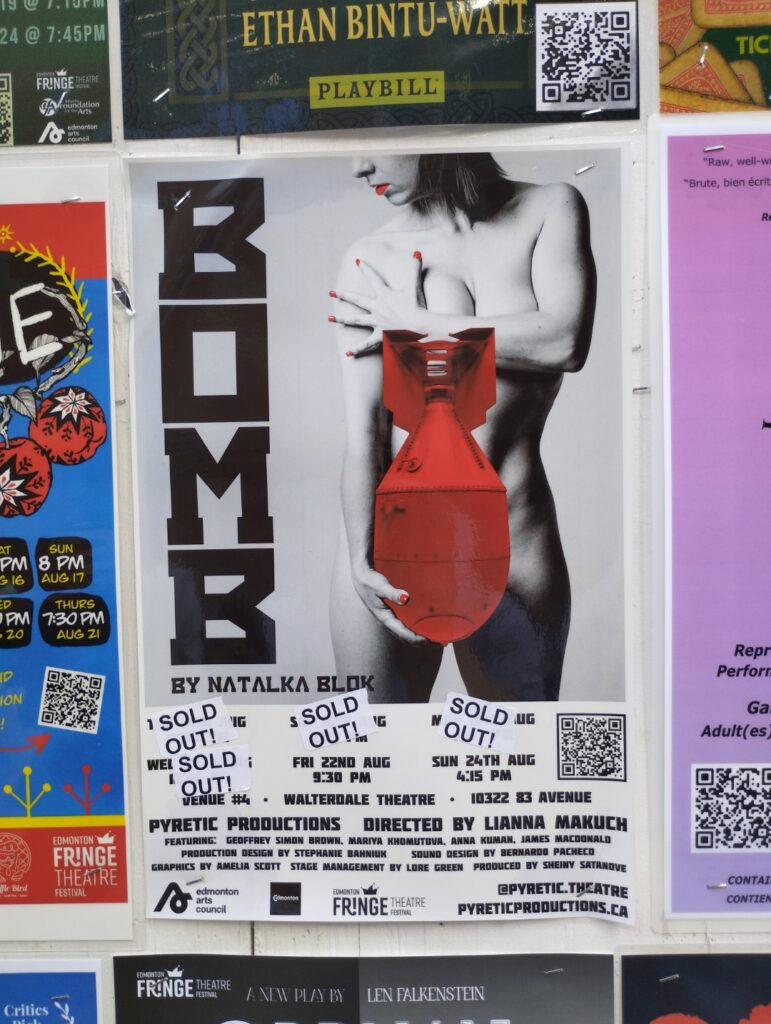

MacEwan Fine Arts Walterdale Theatre (Venue 4)

Runtime: 60 minutes

★★★★☆ 4/5 stars

“Today, I initiated a phone call with the president of the Russian Federation. The result was silence. Though the silence should be in Donbass. That’s why I want to address today the people of Russia. I am addressing you not as president. I am addressing you as a citizen of Ukraine.”

This is how Volodymyr Zelenskyy began his speech, just days before Russia unleashed a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. At the time, thousands of troops were lined up at the border, missiles were trained on targets across the country, and an industrial spectre hung in the pit of every stomach. Already, the invasion was not some amorphous event in a textbook. It was a premonition that every person in the country swallowed and carried with them inside.

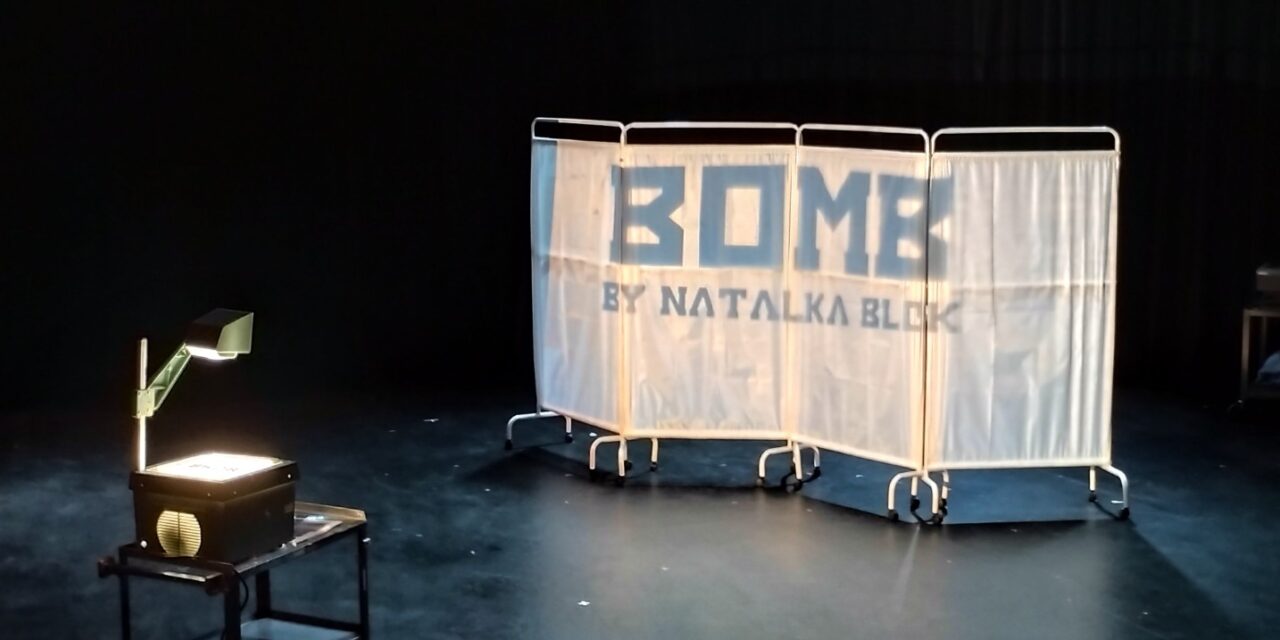

On Monday night, this same spectre enveloped the stage of Natalia Blok’s Bomb. Even from the title sequence, one could feel the material density of Ukraine’s history constrict the stage from all sides. This is the first remarkable feat that Bomb achieved – it distilled the texture and weight of an invasion across all four dimensions of the stage. With the light of an overhead projector, and a set made of nothing more than four medical curtains and some stools, the actors evoked every scene in a kind of clinical-dystopian puppet theatre. Images of auratic x-rays, stencils of missiles, and man-made television static engraved the production’s setting like a retinal scar.

The second remarkable thing that Bomb achieved was its mood, a kind of panoptical psychosis that cauterized around the magnificent sound design by Bernardo Pacheco. Ominous, mechanical, and claustrophobic, every sample was a work of real craftsmanship. The sound was actually so good that the production felt rather bare when it was gone.

The story of Bomb is set in 2017, before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and stands like a bookmark in time; an omen of what was to come. The action follows Dasha (Mariya Khomutova), a Ukranian activist in her 30s who is wracked by PTSD and generalized anxiety. At first, her mental health is pathologized, in a rather mundane way, as she presents her situation to the audience like a one-woman show. She expresses her anxiety, remembers her diagnoses, rails in frustration at the loss of libido, and the play reads like a darkly humorous account of the incompatibility between trauma and sexuality. However, as the production opens up, these prognoses transform and become literal. Her psychotic gestalt therapist (James MacDonald) diagnoses her with the rare condition of a bomb in the pit of her stomach. This is no ordinary bomb, but one with the capacity to rewrite history and save her country.

The metaphor of a bomb functions on three levels. First, it is a tacit reference to the 1994 Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances, which saw Ukraine give up its nuclear arsenal for a guarantee against threat from Russia, USA and the UK. Obviously, this agreement was not honoured some 20 years later. Second, the bomb is a kind of medicalized psycho-anthropological reduction of Dasha’s mental health under the gaze of a mechanical world. Finally, the bomb is a kind of war-cry of latent revolution. Characters implore Dasha to use the bomb, while her husband (Geoffrey Simon Brown) begs her to diffuse it and return to their normal life together. But Dasha is an activist, and her decision hangs in the delicate balance between self-sacrifice and compassion. This third interpretation is where the symbolism of the play becomes strange, and possibly self-ironic. The bomb’s existence is said to reflect a kind of ethnic Ukranian purity, which can be ruined through any love or sex with a Russian. This bizarre conceit seems to reflect the open tear in Ukraine’s post-Soviet history as the country fights to define itself as independent from its monolithic neighbour.

The cast of Bomb is as strong as its jet-fuel script, with special credit due to Mariya Khomutova. Her live-wire performance was the lynchpin of this play and never dropped its intensity, clarity, or authenticity for a second. She felt at home on stage, and bore her character with a hundred-yard stare and directness that felt like someone who had been to the front lines: never conceited – always real.

The play, itself, is written by Natalia Blok, who fled Ukraine in 2022 and currently writes and directs in Basel. Her work is shown all over the world, and will surely end up someday in anthologies of wartime theatre from our age. The writing in Bomb is natural and impressively cyclical in its ability to tie symbols back together on multiple wavelengths. The limitation of the script is its exposition. Sometimes, in lieu of an adequate symbol, Blok’s characters resort to describing their situation to the audience like a thin synopsis. This process lags the production’s frenetic energy, especially in the play’s first monologue, and in frequent explanations used to make sense of Bomb’s strange sci-fi elements.

The expression ‘make sense of’ bears repeating here, because Pyretic Productions’ program lists Bomb as an absurdist work. In its present form, this is not really the case. About half of the play reads like a realist drama about sexuality, trauma and conflict. In this half, the ‘absurd’ elements are really just inventive and impressive theatrical devices that are laced into the production. The other half of Bomb reads like a Kafkaesque bureaucratic nightmare fueled by several deus ex machina plot elements. In many ways, these sections are reminiscent of Terry Gilliam’s 1985 film Brazil, but the expository tendencies of the script basically neutralize the confusion of each ‘absurd’ encounter. We are always given an adequate explanation of how things are happening. Even the bomb, although it is sometimes treated literally, is largely allegorical; more of a dream-reading of Dasha’s situation from a quack psychoanalyst than a real object.

Nonetheless, everything works quite well in this production, largely because of the seamless directing vision from Lianna Makuch. The play is obviously a labour of love, and I encourage any theatre-goer to cross their fingers and watch to see if the play gets held over. The festival run is, understandably, sold out.