Review and photos by Levi Kettner

The fast-flowing rivers of the Canadian Rockies represent the beauty and tranquillity of our unique landscape. The swirling eddies of the Athabasca and the white-capped waves of the Sunwapta draw photographers from across the world, hoping to accurately translate their natural magic into still images. These waterways come to reflect not only the grace of the natural environment but also the interconnectedness of the land and its people.

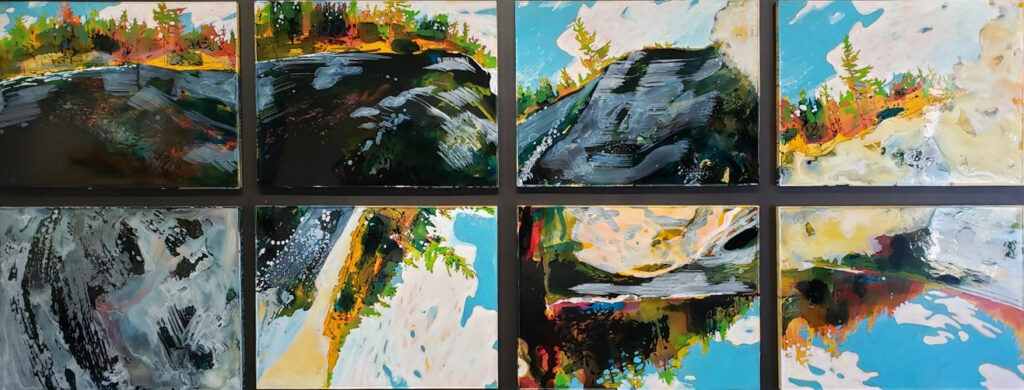

In his latest exhibition at the Peter Robertson Gallery, Ontario artist Steve Driscoll provides art lovers with a new, less tranquil, perspective of moving water. His series incorporates water as a part of an imaginative medium: The observer is no longer limited to the outsider’s perspective as the frame and the viewer become lost within the disorientation of the river’s movements. The strokes on the glossy canvas mirror the sights of a subject who is drowning in the frothing waters. The paintings throw the observers into a frame of reference that most people—hopefully—never experience.

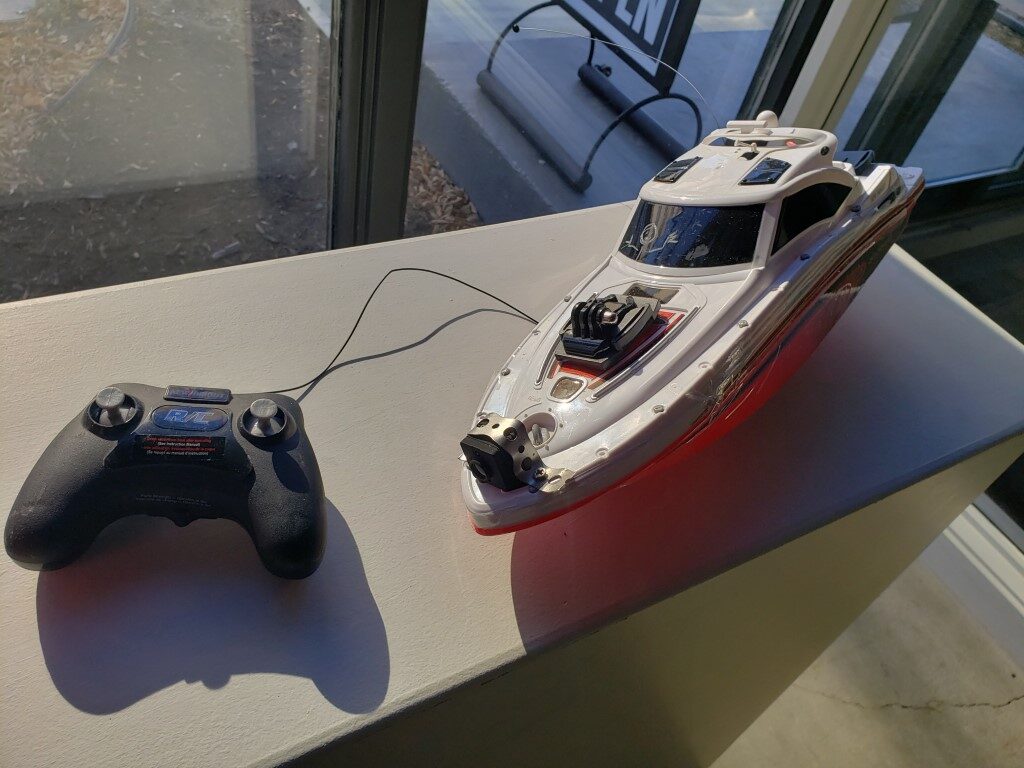

To accurately capture this natural phenomenon in his work, Driscoll recruited the help of modern-day technology: GoPro cameras were attached to different types of flotation devices and sent down riotous waterways. This juxtaposed relationship between technology and nature granted the artist access to the ever-fluxing perspective. Using these images as inspiration, Driscoll translated the GoPro’s captured images through his own artistic vision, and the result was the exhibition River Rising.

The Peter Robertson Gallery, located just outside of the downtown core, is not unfamiliar with Driscoll’s paintings. In 2016, the PRG hosted the artist’s exhibition And a Dark Wind Blows—a beautiful arrangement inspired by the flaring lights of the aurora borealis and night sky. For that installment, the gallery floor was flooded with over 11,000 litres of water to create a reflexive view of the paintings as though the viewer was looking at the night sky over a still mountain lake. Five years later, however, and the illustrated waters mounted on the gallery walls were anything but still.

Part of the beauty of hosting works by artists like Steve Driscoll is the scope of their outreach. Exhibitions like River Rising take their inspiration from nature and can attract appreciators from far beyond the world of art. They can appeal to nature lovers and outdoor sports enthusiasts just as they can to lifelong admirers of fine art. Such collections canserve as a passionate gateway into local gallery scenes and help broaden the art community’s reach.

I was compelled to see River Rising, to be perfectly honest, more as a white-water lover than an art enthusiast. Much of my free time in the summers is spent admiring the currents of a river from a boat and—at times—out of the boat. I partly understand, then, the frenzied desperation that Driscoll’s images capture. The pure chaos and uncertainty that swimming white-water evokes is unmatchable by any other feeling. By visiting the gallery, I wanted to see how Driscoll represented this affect.

The artworks of River Rising and the ambience of the PRG perfectly complemented and contrasted one another. The open concept of the gallery allowed daylight to shine through its windows, helping to illuminate the pieces hanging on the walls. The space was welcoming, exposed, and neutral. Within this shelter, it is clear that Driscoll’s works used the natural light to their advantage. As a result, each work felt distinct and purposeful—never did a frame blend into its surroundings.

As his medium, the artist specializes in creating canvases of industrial urethane—a material commonly used as clear sealant for hardwood flooring. Driscoll mixes pigments into the poured layers of urethane, allowing him to manipulate the colours and textures of the painting. This unique process requires a truly dynamic production method as the paint interacts differently depending on how dry the urethane is when the brush is applied. Since the artist works as the medium dries, each individual piece is completed within a single, prolonged session.

So, for Driscoll, the canvas itself is his own creation. The result is a stunning, translucent canvas that accentuates the vivaciousness of the work’s colours. The series seems so fitting for an autumn viewing, as much of River Rising appears to play on the reds and yellows found in the dying leaves of Ontario’s hardwood forests or, correspondingly, the river valley just outside of the gallery. Driscoll even frames some of his works with LED backlights to help create an effect of luminescence, and although they’re not needed to draw the colours out of the canvas, they nonetheless highlight every vivid stroke of his brush.

Staring at the works of art, the static form comes alive into an undeniable movement. The foam of the white-water is blurred and confused, while the backdrop is often angled, upside-down, or completely unidentifiable. They sent me back to those scary moments of fighting for air and struggling against the brute, rhythmic forces of fast-flowing water. The paintings precipitated the tumultuousness of being thrashed around, confused and delirious, not knowing up from down inside the inaccessible chaos of churning currents. They, in my opinion, threw the observer into not only the view but also the feeling of swimming white-water.

The ingenuity of his creative process is uniquely embodied within each piece. Turbulence well demonstrates the playfulness of Driscoll’s medium. The painting occupies a brief moment during descent into unpredictable delirium. The long, blurred strokes of the current, buried deep within the urethane, educe the feverous motion of the water as it pours over an edge. The sporadic, defined splash of whitewash adds to the perceptible three-dimensionality of the work.

The whole piece—the rushing water, the piling foam, and the hazy shore—is tainted with a red tinge, evoking the impending violence of an uncontrollable force. Everything within the frame—every colour, texture, and brushstroke—seems to fit innately to the tone of its entirety.

One of the larger paintings in the exhibition, River Rising 5, spanned almost the entire height of the wall. The work is composed of an identifiable wave of whitewash—an unstable mess of bubbles and anxiety curling across the frame. But in the centre lurks a backdrop of indiscernible darkness. The wave guards this enigma, protecting it from any focused intrusion, not letting known if what is concealed is nothingness or merely the unknown.

Near the entrance to the gallery, imprinted on the wall, are some words by Bill Clarke. He writes that although the idea for River Rising came before the pandemic, the works have nonetheless come to reflect the uncertainty and turbulence that we have undergone since its beginning. And, as Clarke suggests, even though the paintings are disturbed by the clashing waves of white-water, there is always hope for forthcoming calm waters.

On November 6, the Peter Robertson Gallery opened for its next exhibition, Gregory Hardy’s Shimmer and Boom. If it is anywhere near as captivating as River Rising, I may return to the PRG simply as an art lover.

Peter Robertson Gallery

12323 104 Ave NW

780-455-7479

website