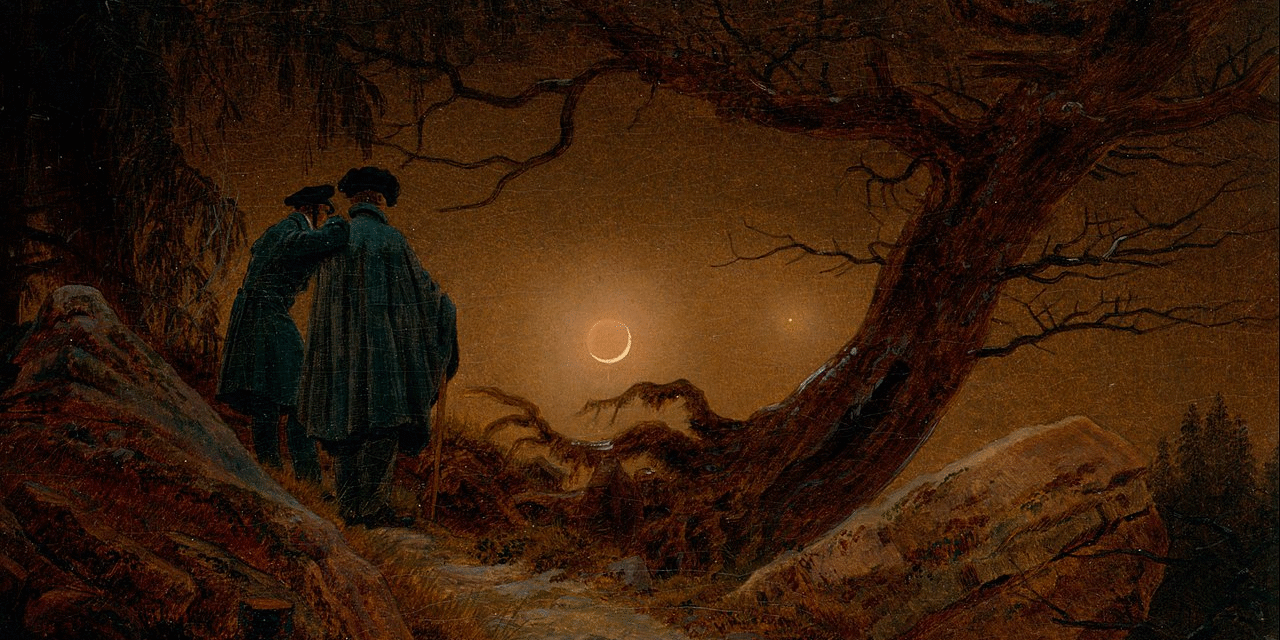

Caspar David Friedrich Two Men Contemplating the Moon (1819-1820)

Review by Mark Morris

Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725) ‘Già il sole dal Gange’

Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835) ‘Vaga luna che inargenti’

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) Sonnet XXXVIII ‘Rendete agli occhi miei’ from Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo, Op. 22

Franz Schubert (1797-1828) ‘Der Wanderer an den Mond’ / ‘Der blinde Knabe Wanderers’ / ‘Nachtlied I’

Richard Strauss (1864-1949) ‘Ständchen’

Kyrylo Stetsenko (1882-1922) ‘Blooms and Tears’

Yakiv Stepovyi (1883-1921) ‘Soon the Sun Will Laugh’

Stanislav Lyudkevych (1879-1979) ‘A Memory’

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) ‘The Water Mill’

Michael Tippet (1905-1998) Boyhood’s End

Florence Price (1887-1953) Clouds

Steven Coxe (b. 1966) Across the Universe

Errollyn Wallen (b.1958) ‘About Here’

Benjamin Butterfield (tenor)

Leanne Regehr (piano)

Edmonton Recital Society

Holy Trinity Anglican Church

January 18, 2026

Ben Butterfield has had an illustrious career as one of Canada’s best known tenors. He has sung internationally, from the Lincoln Centre to Taipei’s National Concert Hall, from the Welsh National Opera to New Zealand’s Canterbury Opera, from the Canadian Opera to Il Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. He has been an influential teacher, notably at at University of Victoria, where he is Head of Voice, and as a former faculty member on Edmonton’s Opera Nuova.

His especial contribution in Canada and abroad has been his performances of oratorio and song, from touring Europe with Trevor Pinnock and the English Concert, to Britten’s War Requiem with the London Symphony Chorus and the State Orchestra of Thessaloniki, not to mention Tafelmusik and Canadian orchestras.

He is thus no stranger to Edmonton. In the days when Edmonton Opera did full operas in the original in the Jubilee, he sang in Der Fledermaus in 1996, The Pirates of Penzance (2000), Cosi Fan Tutti (2001), and The Mikado (2003). There was also a memorable Edmonton Recital Society recital in the Muttart Hall in 2014, where with pianist Peter Dala he juxtaposed performance of Beethoven’s pioneering song cycle An die ferne Geliebtle with Britten’s Winter Words and Randy Newman songs.

He returned on Sunday January 28 for a recital for the Society, currently celebrating its 20th anniversary, at Holy Trinity Church, together with Edmonton pianist Leanne Regehr, who has regularly worked with him. Their program was themed and inventive, titled Sun, Moon, and Stars, traversing repertoire from the 17th Century to the present day, with texts – and one purely piano piece – on just those subjects.

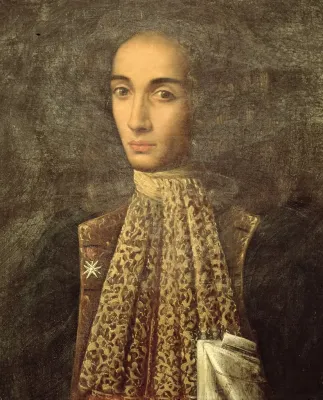

(photo Edmonton Recital Society)

I am lucky enough to have known Butterfield for almost 39 years – we were both at the Banff Centre for its opera program in 1987. He was a young singer just embarking on a career, and I, newly arrived in Canada, ended up directing him in a new opera there. Time has not diminished his wonderful qualities: not just his vocal prowess, but his palpable enthusiasm, his infectious good humour, and his rapport with his audience. His is a lyric tenor, very much in the modern British style of the lighter tenor voice so promoted in the works of Benjamin Britten, but well capable, as he showed here later in the recital, of larger darker tones. He is not a singer in the tradition often encountered in lieder, of a detached immersion in the music – on the contrary, his approach is more dramatic, more directly involving the audience. In short, he is a lieder story-teller.

He set the mood characteristically with a light-hearted song by Alessandro Scarlatti, singing the praises of the sun shining over the Ganges, ‘Già il sole dal Gange’. It actually comes from an otherwise-forgotten opera, L’honestà negli amori (Honesty in Love Affairs), written in 1680 when Scarlatti was 19. He and Regehr then launched without a break into the next song. Grouping songs in recital, and thus avoiding repeated applause, is such a relief (as Butterfield himself suggested), putting the emphasis more on the music and the poetry and less on the performer. Equally commendable is supplying the audience with the full texts and translations, even if it does mean some rustling on page turning – I have never understood how anyone can get the full import of songs and song cycles without knowing what the singer is actually singing about.

That next song was Bellini’s well-known and lovely ‘Vaga luna che inargenti’ (‘Lovely moon, shedding silver’), a bel canto salon arietta, probably written in Milan in the 1820s, just as Bellini was just getting known for his operas. It was a good choice, for the light lifting tone that Butterfield can produce so suits the music and the words – I have heard heavier tenors sing this, and that doesn’t fit the gossamer music and text.

The song equates the moon with love and with longing, and some of the songs in the recital inevitably see love and longing in terms of nature: Britten’s setting of Michelangelo’s Sonnet XXXVII asks nature for respite from being love-lorn, and in Strauss’ marvellous Ständchen “The nightingale above us/Shall dream of our kisses”. Many of the rest, given the recital’s theme, looked at human existence in terms of the natural world around: Schubert through his Wanderer in ‘Der Wanderer an den Mond’ (‘The Wanderer and the Moon’) and ‘Wanderers Nachtlied’ (‘Wanderer’s Night Song’), Vaughan Williams’ in his Schubert-influenced setting of ‘The Water Mill’, the last of the1925 song cycle Four Poems by Fredegond Shove (another song so ideally suited vocally to Butterfield’s colours and tone) – even in John Lennon’s ‘Across the Universe’, in rather a laboured 2013 arrangement by American composer Steven Coxe, with a completely new non-Lennon piano accompaniment.

For those who enjoy art song, this concentration on nature will come as no surprise, since, especially in the 19th and early 20th-century, it was so integral to the human conception of self. But this recital – prompted by that reference to the nightingale – unexpectedly got me wondering whether that whole paradigm is now redundant to generations growing up in mostly urban electronic settings. I can vividly remember when an undergraduate at Oxford walking back to my college at three in the morning from a lover’s tryst, and hearing a nightingale sing in the silent darkened Banbury Road – an amazing experience Strauss would have instantly understood. But how many lovers can now tell of such a thing, and it is noticeable that while popular music of the hippie period was full of nature imagery (think only of ‘Night in White Satin’!), that has largely disappeared from contemporary popular Western culture.

Indeed, the final, contemporary, song seem contrived, in both words and music. Written in 1999 by the prolific British composer Errollyn Wallen, who is currently Master of the King’s Music, the words (by the composer) seem to come straight out of country music:

I sit upon a hillside

Among the redwood trees

I ask for nothing special

But a glimpse of the moon

In the sun

A rare moon

Just grateful for the air out here

And a view of heaven

And a view of heaven

while the music, apart from a piano solo section that seem to take its cue from Dire Strait’s 1981 Telegraph Road, was astonishingly reminiscent of the British song composers writing in the time of the First Word War. In other words, both the poetic style and the music style seem artificial, adopted, and it was rather difficult to believe she has sat on a hillside at night listening to a coyote cry, as I have, and so will have many rural Albertans (I hope she will forgive me if I am wrong).

But that song was very much an outlier in this recital. A surprise was a group of songs by Ukrainian composers – both Butterfield and Regehr are faculty members of of the Ukrainian Arts Song Summer Institute in Toronto, the performance side of the Ukrainian Art Song project, founded in 2004. Its mandate is to catalogue Ukrainian art song and disseminate it internationally – something, of course, that has become more poignant since Putin’s invasion.

All three songs, by composers little known in the West, were very Slavic, tinged with darker fears. ‘Kvity i slozy’ ‘Blooms and Tears’, by Kyrylo Stetsenko (1882-1922) is a setting of Boris Hrinchenko’s 1906 poem that reflects the failed Russian revolution of the previous year:

An awful dream caused

the flowers to cry in the night.

Perhaps they dreamt of us,

Our life without hope,

The blood, the shackles, and the lies,

Our hunger, misery, and cold.’

Optimistic and cheerful at the start, the piano leads it into the darker realms, matched by Butterfield producing the darker tones of his vocal range.

Butterfield was very much the storyteller in the mournful ‘Soon the Sun will Laugh’ by Stetsenko’s contemporary, Yakiv Stepovyi (1883-1921), more so than in his 2010 YouTube recording. There is a link with Schubert’s wanderer here, as the poet tells us that in spite of the sun laughing, he will “carry despair in my heart/ To the ends of the earth”.

The final song in this group was by the most interesting of these composers, Stanislav Lyudkevych (1879-1979). He is probably best known for his symphonic cantata Kavkaz (‘The Caucasus’), a setting of a poem by Shevchenko composed between 1902 and 1913 (the monumentalist finale, titled ‘Keep fighting!’, very much anticipates Soviet Socialist Realism, and can be heard here. A complete performance, in less vivid sound, is here, the music starting at 5’55”). He is also famous for his comment after the Soviet Union had fully taken over Ukraine in 1939: “The reds have liberated us but there’s nothing that we can do about it.” He himself went on to write in the grand Soviet Socialist style, and was appointed a People’s Artist of the USSR in 1969 and a Hero of Socialist Labour in the year of his death aged 100, in 1979. His song ‘Memory’, to a poem by close friend, Volodymyr Starosolsky, was written in 1902, and is tinged with regret, with a darkness underneath.

I can’t claim any of these three songs were major discoveries, but all were impassioned, and the Ukrainian Arts Song Project is a fascinating resource, with access to scores and texts and CDs on a rather difficult to navigate web site (use the three horizontal bars on the top right hand of the first page).

The highlight of the recital, though, was a rare performance of a work that was the most extensive, and the most complex to perform and for the audience to absorb. Michael Tippet’s 1945 12-minute mini-cantata with piano, Boyhood’s End, was composed for that quintessential British tenor, Peter Pears, and his partner, the composer Benjamin Britten. Tippet did little conventionally, and the oddity of this setting is that it is not of poetry, but of prose: a piece written by the Anglo-Argentine author, naturalist, and ornithologist William Henry Hudson (1841-1922), a pioneer of the back-to-nature movement. It comes from his autobiographic Far Away and Long Ago (1918), and is a beautiful meditation on the natural world around him in his childhood in the Argentinian Pampas, looking back to his boyhood innocence: “I want only to keep what I have. To rise each morning and look out on the sky and the grassy dew-wet Earth from day to day, from year to year.”

In structure it uses as a model the Purcellian cantata, with four short but deeply contrasting sections. Throughout, key words are extended in long melismas, and waves flow through the piano writing. The opening is dramatic, operatic (“What, then, did I want? What did I ask to have?”), building to a long held “I want only to keep what I have”. The section section, more meditative, slow and thoughtful, is about climbing trees and nests and eggs, and lying on the water banks watching the water-birds. The third celebrates the pampas as the larger wading birds, a kind of scherzo, and the last gazing up to “white-how, white-bluey sky”. Both in music and in words, it is a powerful peon not only to nature, but to not losing the power of the innocent boy’s wonder at that nature.

This was a persuasive performance, concentrating on the passion of the vocal writing and the angular power of the piano writing, and it was brave of both Butterfield and Regehr to tackle it, and to introduce such a deep-felt work to an audience that was unlikely to have come across it, let alone to have heard a live performance.

The interaction between voice and piano Boyhood’s End is also complex, and the latter is a constant independent commentator. It was very effectively played by Regehr, matching the fluid colours she produced in Strauss’ ‘Standchen’, and it was more than fitting that she should have a piano solo item in the recital.

The five-minute Clouds for piano, by the pioneering Afro-American woman composer Florence Price (1887-1953), was discovered in her unpublished manuscripts as recently as 2009 – it was written some time in the 1940s. Its opening motif of a falling scale-like figure sets the mood for shifting colours and patterns that have an overall regular rhythmic flow which is constantly getting a little interrupted – exactly like clouds. It is also interesting that the influences seem less of the French impressionists, as one might expect, but of the still far-too-little known American impressionists, such as the piano writing of Charles Tomlinson Griffes (for example, the 1915 Pleasure-Dome of Kubla-Khan) which one would have thought she must have known, and perhaps played, in her younger days.

Again, one was grateful for the introduction to the work (and, I suspect, for some to the composer) in this thoughtful, entertaining, and wide-ranging themed recital.

The next Edmonton Recital Society concert features Rafael Hoekman, Julie Hereish, and Dongkyun An in a ‘Bach Cello Extravaganza’ at the Winspear on February 23.

website