Guest student review by Callum Hughes

Having grown up on Vancouver Island, B.C., I was introduced to the indigenous culture at a very young age. Almost all the schools I attended from K-12, 5 in total, incorporated parts of the local tribe’s cultures in their school culture.

My middle school was most active. It was aptly named Quamichan Middle School, the English translation of the local band, Kw’amutsun. A very fascinating class taught there was an introductory course to the Coast Salish tribe, and their people. One aspect of the class was learning to speak Hul’qumi’num’, while another was learning different parts of their culture.

I remember the class was invited to the local long house to witness a very sacred ceremony. To be one of very few Caucasian individuals to experience their culture firsthand is a great honour. Unfortunately, however, the sacredness went unappreciated by my juvenile mind.

Quite frequently, it felt as often as once a month, we would have the elders of each neighbouring tribe come to our school to speak with us. Every time, the topic of residential schools would come up. Despite learning of the atrocities many times, it never gets easier to hear. I will never be able to understand the pain they went through, the pain passed down from generation to generation. To me, the saddest part of residential schools is the lost of one’s culture.

This is what motivated me to review the 2021 Dreamspeakers International Indigenous Film Festival (DIIFF).

It is week-long festival, this year from May 3 to June 7. The festival showcases films from around the world. Given that DIIFF’s mission statement is to: “educate the public about Aboriginal culture, art & heritage”, I was thoroughly excited to watch the various films they streamed. I was not disappointed by what was presented. I found the way the various films touched on the loss of culture to be quite engaging. Now of course not all features covered this aspect, though the ones I will be reviewing did.

Growing up I remember being told countless stories of various indigenous beliefs, folklore, and their overall history. These stories sparked my imagination for a world that had been lost for nearly two-hundred years. From battles between neighbouring tribes, to why the sun rises and sets, I can’t help but envision what the landscapes used to look like. If it weren’t for the elders that would frequent my schools, I never would have been gifted such an insight.

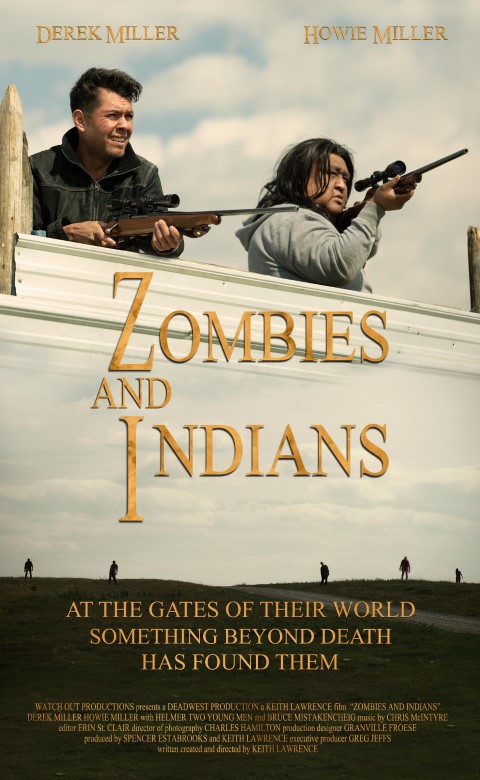

In a comedic fashion, Zombies and Indians illustrates the importance of one’s elders. Directed by Keith Lawrence, with production done by Spencer Estabrooks and Keith Lawrence, this post-apocalyptic comedy was released in 2019. Running only twelve minutes, we are introduced to two men, Kirt (Derek Miller) and Will (Howie Miller), who keep guard to ensure the safety of their reservation. The importance of elders is shown through Kirt’s actions. He has been suffering from a reoccurring nightmare of a traditional warrior dancing, though Will believes them to be visions. Eventually a cart-pulling elder shows up at the gates, pleading in his native tongue. Kirt’s lack of ability to understand what the elder is saying symbolizes his lack of connection with his culture. Eventually, though with hesitation, Kirt lets the elder in, while Will staves off impending zombies.

The short culminates with Kirt unveiling the contents of the cart, though in a style made famous by Tarantino, with his “nightmares” being resolved. Traditional elders are supposed to be the ones who teach the children about their history, their culture, and their folklore. Since Kirt does not understand the elder, this symbolizes his lack of connection with his heritage, and culture. This point is hammered home when, after Kirt opens the gates to let the elder in, letting him into his life, Kirt’s nightmares vanish.

Zombies and Indians did a phenomenal job at covering a heavy topic through comedy and entertainment, in only twelve minutes.

Her Water Drum, directed by Jonathan Elliot, produced by Erica Orofino and Jonathan Elliot, and released in 2018, has a runtime of only sixteen minutes. The film follows a grieving mother, Jolene (Nadia George), and son, David (Michael Riley), as they struggle holding on to hope of finding their missing daughter/sister, Kira (Chanin Lee); her water drum is the only thing they have as a reminder of her.

On the surface, Jonathan Elliot directs a sorrowful film about the missing, and murdered, indigenous women and girls. However, the importance he puts onto the daughter’s water drum, and her traditional music, makes me believe there is an underlying message being told. A message pertaining to the importance music has with the connection of self, along with ones culture. Since Kira appeared to be the musical member of the family, and the one most in touch with their traditional culture, once she goes missing, her mother and brother no longer have a connection with that culture.

Throughout the short film both Jolene and David are both handling the loss of their relative/culture differently; its only at the end when they get some mercy. They end up playing Kira’s CD, which is her singing and playing traditional Mohawk music. Ostensibly, on hearing the voice of their loved one again, they are able to move forward, but I believe that as soon their culture is reintroduced to their lives, are they then able to heal. This short film was beautifully directed and written, in such a way that there are two, equally as important, messages being portrayed. Whether you watch it at face value, or you watch it with a deeper lens, you will be moved emotionally.

The City of Totems, which is the nickname of Duncan – my hometown – is home to forty-four different totem poles located around the city. Each of these massive pieces of art is stunning to look at. All hand carved from cedar logs and painted the colours of the of the Cowichan tribe, these pillars of history enrich the town’s indigenous culture. As a kid I thought they were always there, though with age comes knowledge, and I learned that the first one was erected in 1986.

In the mid 1880s the Christian priests convinced the Haida nation to burn all existing poles, and to cease carving new poles. This, they said, meant they could be allowed into heaven when they died. Eventually all the poles were burned, and the cultural spirit of the Haida people was crushed.

Robert Davidson is a Haida carver, and in August 1969 he carved his most important, and meaningful, piece of art: the first totem pole erected in the village of Old Masset in one hundred years. The documentary, Now is the Time, directed by Christopher Auchter, describes Robert’s reasoning behind carving the totem pole, and what it meant to those on Haida Gwaii.

Not until Robert was sixteen did he hear his first Haida song. Realizing there wasn’t much the elders were able to connect with, he wanted to create an occasion to celebrate. He carved a totem pole with the plan to teach his elders something about their culture. On the day the pole was raised, Robert was thoroughly surprised at how great a turnout there was. Instead of him teaching the elders, they were the ones to do the teaching.

With a pre-existing appreciation for totem poles and for indigenous art, I was moved to see how meaningful the pole was to the people of Old Masset. This pole was the first grasp of Haida culture that the town, let alone Haida Gwaii, had seen in over a century. Director Christopher Auchter superbly captures the importance in the eyes of the elders. Their excitement, and glee for the occasion was beautifully cemented in history by his documentary.

I went into the Dreamspeakers International Indigenous Film Festival already with a great appreciation of, and interest in, various indigenous cultures from around the world. I left with an even greater appreciation, and a hunger to learn more of their cultures. The three films I reviewed did a fantastic job at expressing a different aspect of culture, as well as how showing the lost state of people without their heritage. I highly encourage those with no prior knowledge of indigenous cultures to watch the three pieces; I have no doubt they will develop a hunger for more.

Dreamspeakers Festival Society website

for Pip Pomroy’s review of other movies in the 2021 Festival, click here.

Recent Comments